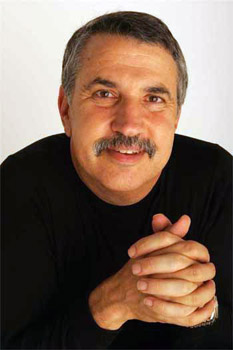

Thomas L. Friedman is an internationally renowned author, reporter, and, columnist—the recipient of three Pulitzer Prizes and the author of seven bestselling books, among them From Beirut to Jerusalem and The World Is Flat.

Thomas L. Friedman is an internationally renowned author, reporter, and, columnist—the recipient of three Pulitzer Prizes and the author of seven bestselling books, among them From Beirut to Jerusalem and The World Is Flat.

Thomas Loren Friedman was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on July 20, 1953, and grew up in the middle-class Minneapolis suburb of St. Louis Park. He is the son of Harold and Margaret Friedman. He has two older sisters, Shelley and Jane.

Harold Friedman was vice president of a ball bearing company, United Bearing, started by a friend after World War II. Margaret Friedman, who served in the U.S. Navy in World War II and studied home economics at the University of Wisconsin, was a housewife and a part-time bookkeeper. Harold Friedman died of a heart attack in 1973, when Tom was nineteen years old. Margaret Friedman, who was also a Senior Life Master championship bridge player, died in 2008.

Fun fact: St. Louis Park was immortalized in the 2009 Coen brothers movie, A Serious Man. Friedman, Ethan and Joel Coen, Senator Al Franken, political scientist Norman J. Ornstein, NFL football coach Marc Trestman, and Harvard University philosopher Michael J. Sandel all grew up in or near St. Louis Park in the 1960s—and most of them went to St. Louis Park High School and the local Hebrew school. The Coen brothers once compared St. Louis Park to the small region in Hungary that had produced numerous nuclear physicists and Draculas.

From an early age, Friedman, whose father often brought him to the golf course for a round after work, wanted to be a professional golfer. He was captain of the St. Louis Park High golf team; at the 1970 U.S. Open at Hazeltine National Golf Club, he caddied for Chi Chi Rodriquez, who came in 27th. That, alas, was as close as Friedman would get to professional golf. In high school, however, he developed two other passions that would define his life from then on: the Middle East and journalism. It was a visit to Israel with his parents during Christmas vacation in 1968–69 that stirred his interest in the Middle East, and it was his high school journalism teacher, Hattie Steinberg, who inspired in him a love of reporting and newspapers. On January 9, 2001, after Steinberg’s death, Friedman celebrated her in his New York Times column:

“Hattie was the legendary journalism teacher at St. Louis Park High School, Room 313. I took her intro to journalism course in 10th grade, back in 1969, and have never needed, or taken, another course in journalism since. She was that good. Hattie was a woman who believed that the secret for success in life was getting the fundamentals right. And boy, she pounded the fundamentals of journalism into her students—not simply how to write a lead or accurately transcribe a quote, but, more important, how to comport yourself in a professional way and to always do quality work. To this day, when I forget to wear a tie on assignment, I think of Hattie scolding me . . . Hattie was the toughest teacher I ever had. After you took her journalism course in 10th grade, you tried out for the paper, The Echo, which she supervised. Competition was fierce. In 11th grade, I didn’t quite come up to her writing standards, so she made me business manager, selling ads to the local pizza parlors. That year, though, she let me write one story. It was about an Israeli general who had been a hero in the Six-Day War, who was giving a lecture at the University of Minnesota. I covered his lecture and interviewed him briefly. His name was Ariel Sharon. First story I ever got published. Those of us on the paper, and the yearbook that she also supervised, lived in Hattie’s classroom. We hung out there before and after school. Now, you have to understand, Hattie was a single woman, nearing 60 at the time, and this was the 1960s. She was the polar opposite of ‘cool,’ but we hung around her classroom like it was a malt shop and she was Wolfman Jack. None of us could have articulated it then, but it was because we enjoyed being harangued by her, disciplined by her and taught by her. She was a woman of clarity in an age of uncertainty.”

After graduating from high school in 1971, Friedman attended the University of Minnesota and Brandeis University, and graduated summa cum laude in 1975 with a degree in Mediterranean studies. During his undergraduate years, he spent semesters abroad at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the American University in Cairo. Following his graduation from Brandeis, Friedman attended St. Antony’s College, Oxford University, on a Marshall Scholarship. In 1978, he received an M.Phil. degree in modern Middle East studies from Oxford. That summer he joined the London Bureau of United Press International (UPI) on Fleet Street, where he worked as a general assignment reporter.

While in England, Friedman met Ann Bucksbaum of Des Moines, Iowa. Ann, after graduating from Stanford with a B.A. in economics, was attending the London School of Economics. They were married in London on Thanksgiving Day 1978. Ann’s father, Matthew Bucksbaum, along with his two brothers, founded General Growth Properties in Des Moines, and built the company into an international shopping mall REIT.

Friedman spent almost a year reporting and editing in London before UPI dispatched him to Beirut as a correspondent in the spring of 1979. He and Ann lived in Beirut from June 1979 to May 1981 while he covered the civil war there and other regional stories. The Beirut assignment was his introduction to life as a foreign correspondent. “In those days, working for UPI, you had to do everything—file a breaking news story, do a radio spot, file a picture, and duck for cover,” he recalls. “It was a great learning experience. The best journalism school there is, in fact. In my little spare time, I played golf at Beirut Golf and Country Club. It had thirteen holes and the driving range was adjacent to a Palestinian firing range. Being in a ‘bunker’ there was sometimes a relief.”

In May 1981, Friedman was offered a job by the legendary New York Times editor A. M. Rosenthal. He left Beirut and joined the staff of The New York Times in Manhattan. From May 1981 to April 1982, Friedman worked as a general assignment financial reporter for the Times. He specialized in OPEC and oil-related news, which had become an important topic as a result of the Iranian revolution.

In April 1982, he was appointed Beirut Bureau Chief for The New York Times, a post he took up six weeks before the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. For the next two-plus years, he covered the extraordinary events that followed the invasion—the departure of the PLO from Beirut, the massacre of Palestinians in Beirut’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, and the suicide bombings of the U.S. embassy in Beirut and the U.S. Marine compound in Beirut. He also covered the aftermath of the Hama massacre in Syria, where the Syrian government leveled part of a town, killing thousands, to put down a Muslim fundamentalist insurrection. For his work, he was awarded the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting.

In June 1984, Friedman was transferred to Jerusalem, where he served as the Times‘s Jerusalem Bureau Chief until February 1988. There, his and Ann’s two daughters were born: Orly in 1985 and Natalie in 1988. It was a relatively quiet time in Israel, but in the West Bank and Gaza the first Palestinian intifada was brewing. Friedman devoted much of his reporting to those two simmering volcanoes, which would erupt right at the end of his tour. As a result of his work, he was awarded a second Pulitzer Prize for international reporting and was granted a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship to write a book about the Middle East.

The book was From Beirut to Jerusalem. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in June 1989, it was on the New York Times bestseller list for nearly twelve months and won the 1989 National Book Award for nonfiction and the 1989 Overseas Press Club Award for the best book on foreign policy. From Beirut to Jerusalem has been published in more than twenty-five languages, including Japanese and Chinese, and is still used today as a basic textbook on the Middle East in many high schools and universities. Although Friedman often joked over the years that he was going to update the book with a new edition, consisting of one-page, one-line—”nothing has changed”—he in fact updated it twice. Once after the Oslo Peace Accords were signed and again in 2012 in the wake of the “Arab Spring.”

In January 1989, Friedman started a new assignment as the Times’s Chief Diplomatic Correspondent, based in Washington, D.C. During the next four years he traveled more than 500,000 miles, covering Secretary of State James A. Baker III and the end of the Cold War. “Journalism involves a lot of luck—being in the right place at the right time and then taking advantage of it,” he once recalled. “I was very lucky to be in Lebanon when it became a dramatic global story, and I was very lucky to be on Jim Baker’s plane to have a front-row seat for the end of the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet empire, the first Gulf War, and the aftermath of Tiananmen Square.”

In November 1992, Friedman shifted to domestic politics with his appointment as the Times‘s Chief White House Correspondent. In that role he covered the post-election transition and the first year of Bill Clinton’s presidency.

“That was really Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride,” he recalled. “It was a great learning experience to see the world by covering the White House. It was different from the State Department. It involved much more politics. But doing it for a year was quite enough for me. I was not cut out to be a White House correspondent, which is a strange cross between babysitting and reporting.”

In January 1994, Friedman shifted again, this time to economics, and became the Times‘s International Economics Correspondent, covering the nexus between foreign policy and trade policy. “Again, I got lucky,” he recalled. “It was the start of the post–Cold War era: the walls were coming down all over the world. The Internet and World Wide Web were being born, and so too was this new phenomenon called ‘globalization.'”

In January 1995, Friedman took over the New York Times Foreign Affairs column. (Click here for his first column.) “It was the job I had always aspired to,” he recalled. “I had loved reading columns and op-ed articles ever since I was in high school, when I used to wait around for the afternoon paper, the Minneapolis Star, to be delivered. It carried Peter Lisagor. He was a favorite columnist of mine. I used to grab the paper from the front step and read it on the living room floor.”

Friedman has been the Times‘s Foreign Affairs columnist since 1995, traveling extensively in an effort to anchor his opinions in reporting on the ground. “I am a big believer in the saying ‘If you don’t go, you don’t know.’ Going doesn’t guarantee you will get things right, but it does reduce the odds that you will get things wrong.” I tried to do two things with the column when I took it over. First was to broaden the definition of foreign affairs and explore the impacts on international relations of finance, globalization, environmentalism, biodiversity, and technology, as well as covering conventional issues like conflict, traditional diplomacy, and arms control. Second, I tried to write in a way that would be accessible to the general reader and bring a broader audience into the foreign policy conversation—beyond the usual State Department policy wonks. It was somewhat controversial at the time. So, I eventually decided to write a book that would explain the framework through which I was looking at the world. It was a framework that basically said if you want to understand the world today, you have to see it as a constant tension between what was very old in shaping international relations (the passions of nationalism, ethnicity, religion, geography, and culture) and what was very new (technology, the Internet, and the globalization of markets and finance). If you try to see the world from just one of those angles, it won’t make sense. It is all about the intersection of the two.”

That book, The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization, published in 1999, won the Overseas Press Club Award for best book on foreign policy in 2000. It has been published in twenty-seven languages. Its central argument was that the globalization system – the ever tightening links of trade, finance and connectivity between countries – replaced the Cold War system – the bipolar world. And that international relations could best be understood as the interaction between, as noted above, all that was old – the forces of nationalism, regionalism, tribalism, ethnicity and sect – and all that was new: this globalization system. Sometimes that globalization system would restrain those urges and sometimes those urges would burst right through the system, but the price countries and leaders would pay who did burst through this system would, he argued, always be higher than they anticipate.

“I think the framework for explaining global affairs that I laid out in The Lexus and the Olive Tree is more valid than ever—this tension between our olive tree urges—our adherence to nationalism, sect and tribe—and the now even stronger globalization system. Yes, sometimes those olive tree urges will drive leaders to strike out—Vladimir Putin will seize Crimea—but, up to now, he has decided not to take Kiev because of the stress that global sanctions have imposed on his country and his fear of an additional loss of investments. That is the Lexus vs the olive tree in a nutshell. In that book, I also defined what I called the “super-empowered angry man” to explain how globalization was empowering small groups and individuals who opposed the system. The person I used as my model was someone called ‘Osama bin-Laden.’ That was in 1999. So I was stunned by 9/11, but not entirely unprepared for it.”

After the World Trade Center was destroyed on 9/11, Friedman wrote many columns about war, terrorism, and the clash of democratic Western societies with fundamentalist Muslim ones. For those columns he was awarded a third Pulitzer Prize—the 2001 award for distinguished commentary for “his clarity of vision . . . in commenting on the worldwide impact of the terrorist threat.” In 2002 FSG published a collection of the columns, along with a diary he kept after 9/11, as Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11.

“Probably the most noteworthy columns I wrote during that period,” Friedman recalled, “were my 2002 interview with Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz, through which he first proposed his Arab-Israeli peace plan, and my columns that supported President George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq. Before going to Saudi Arabia in February 2002, I wrote a column in the voice of President Bush calling on the Arab League to offer Israel full peace, diplomatic relations and normalization of trade in return for a full Israeli withdrawal from all lands occupied in the 1967 war and East Jerusalem. When I arrived in Saudi Arabia a few weeks later I was invited by then Crown Prince Abdullah to his ranch outside Riyadh at midnight. There was only himself and his foreign policy aide Adel al-Jubair (now the Saudi ambassador in Washington). Adel served as the translator. The first thing the Saudi Crown Prince said to me was that I had ‘broken into his drawer’ and stolen his peace plan idea. He said he had the same idea as I wrote in my column. At the end of a three-hour conversation I asked Abdullah if he would put his proposal, which was the same as my proposal, on the record in my column. He said he wanted to sleep on it. The next day Adel called me and told me it was OK to write it up as an on the record interview. It immediately became known as ‘the Saudi Peace Initiative,’ and after an Arab summit in Beirut embraced it, with some amendments that were not in my original column, it became known as the ‘Arab Peace Initiative.’ Unfortunately, neither Israel nor the United States jumped on the initiative as I had hoped and leveraged it to promote a wider Arab-Israeli peace. Yet, it remains out there today as the only truly pan-Arab peace initiative.”

“My position on Iraq proved particularly controversial with some of my readers, since my support for the war was not based on the belief that Saddam Hussein had any weapons of mass destruction that could threaten us, nor was it based on any affection for President Bush’s other policies,” Friedman recalled. “It was based on my conviction that, in the wake of 9/11, we needed to find a way to partner with Arabs and Muslims in the heart of the Arab world to build a different kind of politics and governance there—a more democratic framework that would give Arabs and Muslims a real voice and say in their future and the sense of dignity and ownership that is the only basis for healthy societies. It was the liberal case for the war. In the run-up to the war, I often cited the maxim that ‘In the history of the world no one has ever washed a rented car.’ For centuries Arabs have been renting their countries from foreign powers, kings, and military dictators, and that has been a key reason for the rampant anger, frustration, and economic underdevelopment of their world. I felt it was crucial after 9/11 to see if in one country, in the very heart of the Arab-Muslim world, we could partner with the people to try to build a self-governing society and a consensual government. Without those things, the pathologies that produced 9/11—the witches’ brew of dictatorship, religious obscurantism, unemployment, and humiliation of people who felt voiceless and left behind by modernity—would just keep threatening this region and the world.

“Nothing has pained me more than to see that the costs of that conflict—which I warned would be very high—have been staggering,” Friedman added. “At times the war was grotesquely mismanaged by the Bush administration, which brought too few troops and too little knowledge of Iraqi society to this giant task of nation-building. Only the combination of the Iraqi tribal awakening and the U.S. military surge managed to bring it back from the brink. Iraq’s final chapter has not been written. If Iraqis can produce a self-sustaining democracy in the heart of the Arab world—one based on an unprecedented social contract between Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds—it could over time have a very positive impact on a region barren of democratic government. If that happens, the Iraqis, Americans, Brits, and other allies, who have paid a huge price for this endeavor, will at least be able to say it produced something decent and better in Iraq. If, however, Iraqis can’t come together and seize this moment, it will all have been for naught—a huge lost opportunity for them and us. I continue to root for Iraqis to succeed, in the hope that real liberty, rule of law, and consensual government will take root in the heart of the Arab-Muslim world but up to now nothing that has happened in Iraq as a result of our intervention could be said to justify the huge human and financial costs that Iraqis, Americans and others have paid – and for that I have nothing but regrets for supporting this huge intervention. After 9/11 I was in a hurry to change the Arab world, to see democracy and pluralism take root there as an antidote to political and religious extremism. I hitch hiked on George W. Bush’s war to promote that democracy. It didn’t work. It had to come from within Iraq and from within Iraqis. And while many Iraqis shared that aspiration – and many Arabs as we would see with the Arab spring – the forces for democracy and pluralism up to now have proven to be just too weak compared to those for sectarianism, revenge – or just stability at any price. You should never be in hurry on behalf of another people – one of the many lessons I took away from Iraq.”

“The takeover of large chunks of Sunni central Iraq and Syria in 2014 by jihadist militiamen from ISIS made the situation even worse, but one of the unanticipated results of ISIS’s rise was that it actually prompted Iraqis—Sunnis, Shiites, Christians, Yazidis, Turkmen and Kurds—to come together to defeat ISIS. Since that victory in 2019, there has emerged in Iraq (and Lebanon) a mass movement, from the bottom up, for more secular, non-sectarian, uncorrupted government. But Iran through its proxies has been doing everything it can – as it did from the beginning of the Iraq war – to prevent a true pluralistic, secular democracy from taking root in Iraq for fear that it would spread to Iran.’’

Friedman’s belief that the Arab world is capable of, in need of and desirous of political pluralism, gender pluralism, religious pluralism, education pluralism and economic pluralism has proven at best premature in Iraq, and many other countries, it did, though, help him see the “Arab Spring ” coming, before it actually erupted in Tunisia in December 2010. On Oct. 23, 2010, Friedman appeared on the Israeli television news show, Meet the Press, where he shared the following prediction with Israeli viewers: “This is how I look at the Middle East today—I look at it as a region that is [experiencing] a huge population youth bulge growing up in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Jordan. I see it as a region, because of oil, that is falling behind every global trend. I think the Arab Middle East is heading for some very significant social and political explosions. That the last 50 years are not going to look like the previous 50 years, as this Facebook generation of Arabs grows up, looks for jobs and seeks political expression. In this kind of Middle East I would love to see Israel behind a wall—as all these things go on—but a wall mutually recognized by Israelis and Palestinians. I think there is going to be turmoil around Israel, that’s how I see the region.”

After spending a great deal of time in the Middle East in the years after 9/11, Friedman decided to do some reporting elsewhere, particularly India. He traveled there in February 2004 to do a documentary for the Discovery-Times channel called, “The Other Side of Outsourcing.” In the making of that documentary I realized that that while I had been sleeping – or rather, while I had been off covering the post-9/11 world, something really big had happened in the globalization story that I first documented in “The Lexus and the Olive Tree.” I felt I really needed to update my own intellectual operating system and software to reflect that change. In April 2005, FSG published his fourth book, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century. The book became a #1 New York Times bestseller and received the inaugural Financial Times/Goldman Sachs Business Book of the Year Award in November 2005. A revised and expanded edition was published in hardcover in 2006 and a Release 3.0 paperback edition in 2007. The World Is Flat has sold more than 4 million copies in thirty-seven languages.

Also in 2007, Friedman wrote the afterword for Classic Shots, a collection of photographs from the United States Golf Association, published by the National Geographic Society.

After 9/11, Friedman began making documentaries for the New York Times–Discovery Channel joint venture. Over the next few years he coproduced, reported, and narrated six documentaries:

“Straddling the Fence” (2003)

“Searching for the Roots of 9/11” (2003)

“The Other Side of Outsourcing” (2004)

“Does Europe Hate Us?” (2005)

“Addicted to Oil” (2006)

“Green: The New, Red, White and Blue” (2007)

In 2008, Friedman published Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution—and How It Can Renew America. It became his fifth consecutive New York Times bestseller, and was cited by the White House as a book that President Barack Obama was reading on his 2009 summer vacation. It has been published in more than a dozen foreign languages. A 2.0 version of Hot, Flat, and Crowded was published in paperback in 2009, with three new chapters exploring the parallels between the climate crisis and the global economic crisis. “While on the surface this sounds like a book about energy and environment, it really isn’t. It is really a book about America,” Friedman explains. “It has become painfully obvious that for a variety of reasons our country has lost its groove in recent years—Washington doesn’t work, our public schools and infrastructure badly need rebuilding. This book was my own contribution for how we can get our groove back as a country. It is by taking on the earth’s biggest challenges—many of which flow from a planet getting hot, flat, and crowded—and leading the world with the solutions and technologies that will meet those challenges head-on. As we enter the second decade of the twenty-first century, I find this set of issues—how we take the lead in the clean-tech revolution and use that to refresh, renew, and revive America—is what animates me most. If there is one overarching theme that drives my column today, it is the need for nation-building in America.”

In September 2011 Friedman published That Used to Be Us: How America Fell Behind in the World It Invented and How We Can Come Back, co-authored with Johns Hopkins University foreign policy expert Michael Mandelbaum. The book was meant to be both a wake-up call and a pep talk for America. It analyzed the four great challenges America faces—globalization, the revolution in information technology, the nation’s chronic deficits, and our pattern of excessive energy consumption—and spelled out what needed to be done to sustain the American dream and preserve American power in the world. Friedman and Mandelbaum argued that the end of the Cold War and the catastrophe of 9/11 blinded the nation to the need to address these challenges seriously. They were confident that America could come back—if it studies, not China, but its own history and the formula for success that made it the richest and most powerful country in the world over the last two centuries. “That used to be us,” they insist—and can be us again. That Used to Be Us was Friedman’s sixth New York Times bestseller. In December 2016 Friedman published his seventh and latest book Thank You For Being Late: An Optimist’s Guide To Thriving In The Age Of Accelerations. It became his seventh New York Times bestseller.

In many ways his most personal book since From Beirut To Jerusalem, Thank You For Being Late argues that the world is being reshaped by the acceleration of three giant forces — “the market, Mother Nature and Moore’s Law,’’ i.e. digital globalization, climate change and technology—in ways that are totally reshaping politics, geopolitics, the workplace, ethics and communities. He explains how these accelerations got so big and fast and how, as a result, we need to reimagine politics, geopolitics, digital globalization, ethics and communities to get the most out of these accelerations and cushion the worst.

In 2013 and 2014 Friedman served as a correspondent for the Showtime network’s climate change documentary series Years of Living Dangerously.The series explored the effects of climate change all over the world, and Friedman participated in four episodes—those exploring climate and environmental impacts on Syria, Yemen, Egypt and in a wrap-up interview for the whole series with President Obama. The show, conceived by David Gelber and Joel Bach, won the 2014 Emmy Award for Outstanding Documentary Series. In 2016, Friedman took part in season two of Years of Living Dangerously, which was aired by National Geographic Television. He and his crew traveled from villages in West Africa, up through Niger and then over to France to track the African refugees who were fleeing small farms and villages that had been hammered by climate change and populations explosions, making them no longer able to generate enough work and income for their populations, who are now fleeing in greater and greater numbers to Europe.

Friedman has won three Pulitzer Prizes: the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting (from Lebanon), the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting (from Israel), and the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary. In 2004, he was also awarded the Overseas Press Club Award for lifetime achievement and the honorary title Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Queen Elizabeth II. In 2009, he was given the National Press Club’s lifetime achievement award.

Friedman and his wife, Ann, reside in Bethesda, Maryland. Ann, who taught first-grade reading in the public school system in Montgomery County, Maryland, is also vice chairman of the board of directors of the SEED Foundation, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., that developed a college-prep public boarding school model for underserved urban students. Ann is also on the boards of Conservation International, the Aspen Institute and the National Symphony Orchestra. In 2015, Ann founded a language arts museum in Washington, D.C., called “Planet Word,” which opens in May 2019 at 13th and K Street. Tom is Vice Chairman. Their elder daughter, Orly, who did Teach for America out of college, was a public school teacher, was Head of Lower School & Assistant Head of School of the Khan Lab School in Silicon Valley, founded her own independent school in San Francisco, the Red Bridge school. Their younger daughter, Natalie, is executive producer of “Weekend All Things Considered’’ on NPR.

Friedman was a member of both the Brandeis University Board of Trustees and the Pulitzer Prize Board, but has since retired from both. He was a visiting lecturer at Harvard University in 2000 and 2005. He has been awarded honorary degrees by Brandeis University, Macalester College, Haverford College, the University of Minnesota, Hebrew Union College, Williams College, Washington University in St. Louis, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Technion, the University of Maryland at Baltimore, Grinnell College, the University of Delaware, Tulane, The Energy and Resources Institute in India and Hasselt University in Belgium.

His golf handicap is a 7.1 index.

Additional biographical links

Profiles of Mr. Friedman: The New Yorker and Washingtonian Magazine

Graduation speeches: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Williams College, Grinnell College, Washington University in St. Louis, the Technion, the University of Delaware

Interview with President Obama on the world for the New York Times: Article, Video